(Scanorama december 1996-januari 1997)

”Paul Zarzyski (the name rhymes with bar and whisky) grew up in a home without books, the son of an immigrant Polish miner. He found literature by way of the rodeo. Before his readings he bends and stretches like an athlete warming up for a sports event. Then he sticks out his big chin beneath a sad-looking droopy moustache. ”Riding bucking horses in the rodeo, you want to stay on their backs for eight seconds. That’s a very long time when the horse is coming apart and boiling over. In my subconscious, I’m still riding bucking horses on the page. For me, every line’s like an eight-second ride and I want those words to jump and kick hard, to rock and roll off the stirrup bone of the middle ear.”

The road to the American West, the real West, never passes Nashville or Hollywood. It runs beyond the grassy hills of the prairies, behind the sandstone sculptures of the deserts, beyond the the reach of TVs and newspapers and out into the empty wilderness.

The 10,000 cowboys and cowgirls who invade little Elko in the high-plateau country of northern Nevada to read poems and dance to wild fiddle music are representatives of a down-to-earth lifestyle, with horse manure under their nails and trail dust on their boots, but they are also members of a vital and rather secretive cultural movement, far out in the back-country of rural America.

They are not the kind of people who beat their own drum. It’s like the cowboy poet Wallace McRae writes:

You got to be dang careful

If you want to be thought smart

And keep sorta confidential

Little things that’s in your heart

From his isolated home in the wilds of Montana, where he still pounds away on a portable typewriter, Paul Zarzyski drives once a year to Elko to enjoy the bonds of intimacy which seem to encompass the Cowboy Poetry Gathering. Here an endangered way of life has found expression. ”You think of the Westerner as an independent, strong-willed person. Yeah, might give that impression once in a while,” Zarzyski says. ”But you come to Elko and the hardest man and the hardest woman will succumb to the spirit and the passion here. It just brings the emotions right to the surface.”

The audience roars its approval when he steps out onto the stage, a rodeo poet whose verses kick and jump in a gyrating torrent of words, as in the poem ”Monte Carlo Express, PO Box 258, 15.3 Miles Home”, which deals with mad trips home from the post office along deserted highways, with the car full of letters and bills:

with 4 white crosses for those who did not

quite make this curve

because of booze, because of snooze, because of

tire or tie-rod act-of-God failure

of car or heart, or the piss-poor

penmanship of a good friend

loving me almost to death with this letter

”Cowboy poetry,” says Waddie Mitchell, a local Elko cowboy and family man who now makes a healthy living from recordings and readings of his own poems, ”is almost like an oxymoron, two words that don’t fit together. Like postal service or military intelligence, the words seem to contradict each other. When we started this festival 12 years ago there wasn’t any given term for what we did. We just did it.”

No one laughs any more, cowboy poetry has come into its own. The myth of the gun-slinging, solitary semi-outlaw is being replaced by the more realistic image of a hard-working cattle raiser who trades poems with his colleagues when the winter blizzards are raging and nothing much is doing on the ranch.

The rhyming wranglers who meet at the Cowboy Poetry Gathering are the heirs to that brief era in modern American history, 1770-1890, which has so strongly captured imaginations and forged ideas about the West (and, by association, about the entire United States). Following the bloody Civil War in the first half of the 1860s, the vast territories west of the Mississippi River were forcibly taken from native American groups and opened up to the expansive industrial culture in the East. Herds of cattle replaced the buffalo on giant ranches, then more settlers arrived and the prairies were gradually fenced in. The mythology of the Wild West arose out of the often lawless struggle for land and power. But it wasn’t the cowboys who chased off the Indians. That battle was fought by the military.

Why do Americans so often seem to seek their ideals in the memory of the Old West? What is it that attracts us in country music and in the Hollywood stereotype of the rootless romantic riding off into the sunset? ”Ours is a new country and out West people are rarely more than two generations removed from a very rural lifestyle. I think it’s still in their blood,” observes Waddie Mitchell, whose poetry, often with a humorous twist, celebrates the simple, basic things in life. ”With the information highway at our fingertips and electronic entertainment in our face all the time, it’s nice just to sit back.”

The cowboy also represents adventure in a time when we strive for security. He embodies a kind of innocent freedom which, for many Americans, and others as well, is an unattainable but alluring goal. But the romanticizing of cowboy life of course disregards the tough day-to-day grind of horses and cattle.

In the midst of all the rattlesnake boots and Stetson hats at the gathering, it’s clearly evident that this is a culture in the throes of change. At a quick glance the gathering may also look like a stage set for a Western movie, but this is only a veneer, a symbol. The environmental debate has penetrated the ranching business and created dissension in the ranks about who’s the best steward of the land, the ranchers or the federal authorities.

The modern cowboy and Indian cultures have become interwoven in the West, with the horse as the common denominator and the rodeo as the meeting place. When representatives of either group talk of their relationship to nature, they seem to be dipping into the same philosophical well for wisdom. Indian cowboys are common west of the Rockies and a natural part of the scene at the Cowboy Poetry Gathering. At night the cowboys and cowgirls dance in the dilapidated clubhouse on Idaho Street to musicians who speak with both Spanish and Navajo accents.

So don’t be surprised when Clara Spotted Elk, Native American cowgirl poet, enters the big stage. What’s most surprising is her way back to the source, the place where the words grow. A few years ago she broke up from an unhappy home in Washington, DC, and moved with her children to a ranch in the outback of Montana. From her windows she can see the red hills which, according to her elderly relatives, were coloured red by the blood of the Cheyenne.

Spotted Elk writes about encounters with the mythology of her people, but also about the loss of her son, a promising bull rider who was killed practising his sport. Her poems are like cries from the wilderness, from the exile and the isolation that is the rural West. ”The old cowboy ballads come from people who were way out on the prairie by themselves watching over cattle. They were lonely and singing was basically a form of self-entertainment. I started writing poems because where I live it’s so isolated that we don’t get any television.”

She views the popularity of country music and the growing interest in a commercialized and sentimentalized cowboy culture as a yearning for the simple life on the part of modern city people. ”Cowboy poetry’s often meant to evoke a love of the land and of the spirit of man. Any people who live close to the land and are dependent upon the weather and other elements can’t help but have a great awe for a higher power.”

But Spotted Elk also feels that the life of the cowboy has been very glamorized. ”When I left home Tuesday morning, it was 43 degrees below zero, my pickup was frozen up. I’d been feeding cattle every day and going out and getting firewood. To tell you the truth, I’m more than happy to leave that behind in Montana for a week and come to Elko and talk about it rather than do it.”

It’s one of the most emotionally charged moments of the Elko festival when Texas cowboy Buck Ramsey, paralyzed after a horse accident, wheels himself onto the stage and reads ”Anthem”, a powerful meditation on man and nature and freedom:

…And as I ride out on the morning

Before the bird, before the dawn,

I’ll be this poem, I’ll be this song,

My heart will beat the world a warning

Those horsemen will ride with me,

And we’ll be good, and we’ll be free

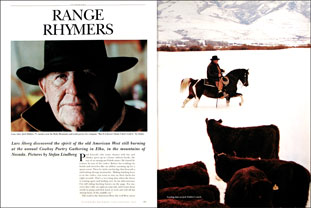

Later, at dawn, after driving an hour through the snowy landscape south of Elko, I meet an old man who still rides out to feel good and defend his freedom. Jack Walther, 77, has lived all his life here at the foot of the mighty Ruby Mountains, on the boundary between alkaline and scrub desert. When the horses have been seen to and are safe in their corral, he sinks down in his poetry-reading chair. ”You’ll find poetry with people who are more or less solitary,” he says. ”They have time to think and comprehend what’s going on. I tend to think about poetry when I’m alone. I like the rhythm of poetry, but if it doesn’t rhyme I don’t even read it. Poetry’s a feeling. To me, the writers who are not inhibited by the rules and regulations of poetry schooling are the true poets.”

The wall clock in the family’s wood-panelled living room marks the passage of time as Walther recites his classical favourites. It smells of coffee and melted snow, and it’s a long way to Brooklyn or Beverly Hills. And I realize, America’s so vast and roomy, there’s at least one viable myth for every dreamer.

As the sun rises towards its zenith, we go out with the sleigh to feed the cattle, almost a thousand brown shaggy cows and yearling calves in a frozen landscape. It’s quite and very peaceful. I sit at the back and slit the straps around the bales of hay and shove them out into the snow.

”I’ve studied the land all my life and I’ve learned a lot,” Walther says in a bluesy voice, ”but I realize that I know very little compared to what there is to be learned. I wouldn’t know what to do if I wasn’t a rancher. I wouldn’t know how to live in town.”

The Cowboy Poetry Gathering is a gathering of strength, a woeful song rising from a culture under siege. For all its vastness, America is also starting to get crowded. More than a hundred years after the end of the cowboy era, the battle for land, water and space is intensifying. There may not be room for the culture of the horsemen, for a lifestyle based on wide-open spaces and poetic journeys through life.

Paul Zarzyski contends that the openness is all-important. When the doors are closed, the cowboy culture will die. It broke the old-time cowboys’ hearts when they started stringing wire on the prairie. ”All of this used to be open range, no fences, no wire. To start fencing the cowboy poetry, trying to box it and define it, is to do it a grave injustice. I consider it the open range of literature.”