Outside, the sky is stretched to its blue breaking-point and the city sends its citizens to the beaches. Millions have been invested in integration projects and inquiries dealing with meeting-places, but when the sun is shining people mix naturally, also in that part of Malmö, on the water´s edge, which when it was first built was seen as isolated and way too fashionable for the common man.

Inside, here on the first floor of the main theatre foyer, the atmosphere is cool and accordingly expectant among the lounge suites. Some of the guests are festively dressed, others wear t-shirts. There is water or sparkling soda in the thin glasses. The panorama windows let the light flow without blinding the people invited.

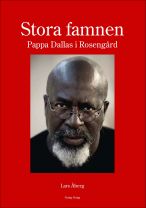

Draped in his golden brown grand boubou with a hat – three layers of rustling fabric that resembles both leather and paper – and with the medal from the Royal Patriotic Association around his neck, Dallas enters and sits down in the first row. He looks like the Emperor of Mali. Music is being played on bozouki, bass, accordion, fiddle and guitar. The chairman of the City Council praises his city hoping that everyone will feel welcome. The theatre manager reads two poems by Hjalmar Gullberg. And then the new citizens from Africa and Asia and Eastern Europe receive their diplomas and local city guides before they line up for herring sandwiches and strawberry dessert. It is the 6th of June, 2008, the Swedish national holiday.

Why did it take so long to become a Swedish citizen?

“I didn´t have the time,” Dallas responds. “I had to take care of all the kids that noone wanted.”

But now it is summer. Soon one of his old novices, a tiny guy who has become a professional with his fists in gloves, will temporarily take over the coaching in the basement hall underneath the Rosengård sports centre. At five in the morning the next day Dallas will be on the train to Copenhagen Airport for further transportation via Bruxelles to Dakar, Senegal. By August he will be back in Malmö. This is how the world is tied together, this how everything becomes a whole.

Of the children, who are clinging on to him in school or shaking his hand at the boxing club, he says that they are all his babies. Of the teenage guys, who more or less flexibly run around sweaty in the training hall, he says that they are all world champions until the opposite has been proven.

“The sun in your heart,” says Dallas. “You gotta have that.”

When he was working at Kryddgårdsskolan in Rosengård, he had classes called “Learn with Dallas”. The teaching has never really come to a stop. He wants the kids to learn about society, they need to know how to eat potato chips without stuffing themselves and that you must have clean underwear and be able to accept a loss.

……