People will tell you that every fourth person in the state of Nevada is living in some sort of mobile home, a trailer with or without wheels. Some of them are stuck in the dirt surrounded by sagebrush. Others are heading, or escaping, down the road.

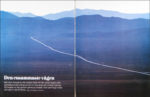

Early mornings in the desert the air is crisp och filled with the smell of sage; everything is water-colour pale and fresh and desolate, like the landscape had been given an airing, as if someone already cleaned out yesterday´s events. You stand there with your stiff hands holding a coffee mug, realizing that it probably is a two-hour drive to the next human being.

It was here, in the Nevada desert, that the government sent out the Light; a fire rolling toward the east, across the defenceless land of the Navajo, and spreading its ashes over isolated Mormon communities, where the faithful would stand at strict attention beneath the Stars and Stripes as the radiation was sucked into their genes. The hairdressers in Las Vegas in the 1950´s offered their fake-blonde customers atomic hairdos, fluffy clouds with a certain elevation. There was something almost kind of festive about the Cold War, like being at a barbecue.

Then came the Darkness. Silenced protests from those whose children were born with faces looking like a cluster of grapes, the Atomic Energy Commission´s cover-up and pursuit of compromising witnesses.

The U.S. military is still testing new weapons in the cactus mountains. And the nuclear waste, eternal by-products of civilization currently being stored at 131 locations in 39 states, is to be deposited in Yucca Mountain not too far from Vegas.

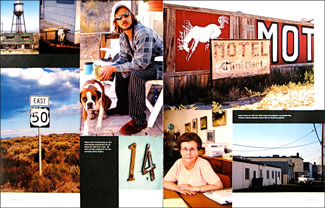

It has been called the loneliest stretch in the whole of America, this road that runs straight across Nevada, Highway 50. Out here, people´s index fingers are gnarled from rattlesnake bites. Here, the wind can be heard rustling between broken boards in deserted cabins and straight through the rickety lives that remain when freedom has been dispersed.

”Come to America. It´s good here.”

Kanji Patel´s two brothers, who had moved to California, wrote letters back to Gujarat in India urging him to join them and, eventually, Kanji and his wife Kusum ended up in Fallon, on Highway 50, where they bought themselves a motel and changed its name from the not completely accurate Uptown Motel. A car seat made for three sits outside our room and on the door one of the digits is loose. The swimming pool looks like a photograph by William Eggleston.

We have come to Fallon by way of the Sierra Nevada, with its dizzying, dusty, meandering roads passing salty lakes and ghost towns from the goldrush years, and in front of us lies the Big Loneliness. An asphalt string all the way to Utah. It is your choice, you are not rooted anywhere, you are ”a prisoner of the fine white lines on the free, free way” in the words of Joni Mitchell from her song ”Coyote”. The call is echoing through the centuries: come to America, it´s good here.

And because, deep down inside, you are all alone when you arrive, you cannot have any expectations of being helpt. The coyote is howling outside the garden boundary where the wilderness takes command.

A huge fire burnt Fallon to the ground in 1910 and in 1954 an earthquake shattered its Maine Street. On one side of town the air force offers jobs and exhibits its show pilots, who dive through thick smoke and swirl around like sparrows in a Caribbean hurricane, and at the other end there are tiny, leaky homes with junk lots and car wrecks and people in undershirts trying to patch up their everyday lives. Hanging electricity lines create cobwebs just like in Mexico.

On television, the president has claimed that he has made America safer by proclaiming a war without end against people unknown to him. In the ”Citizens´ Preparedness Guide”, with a foreword by the Attorney General, all Americans are encouraged to purchase portable generators, store canned foods and toilet paper, be careful with mail in hand-written envelopes and, if they really need to travel abroad, to dress in a discrete fashion and to avoid loud conversations. This sounds like a manual for survival in the desert – or in a society where widespread distrustfulness constitutes a prerequisite when lonely riders show up seeking support for their lone range politics.

Passing between mountain ranges Highway 50 stretches across flat dirt plains, where yellow traffic signs warn of low-flying aircraft and strong gusts of wind. Every now and then white sand is piling up in untouched wave formations. You spot gliding hawks, but never see their prey. Once again, The White House is picking its own course in world politics, beyond or outside international agreements, and those who live out here in the desolation have to mind their own business, too. When the Americans drove off the Western Shoshone Indians from Nevada they were not just looking for gold and silver, but also for seclusion and absence of binding regulations. They wanted to be left alone, doing whatever pleased themselves.

Greg Del Pocco says that he does not pay any other taxes than the one on beer. He helps out with practical chores at the Middlegate Station, which was once built as a stable where the Pony Express riders could change to rested horses, and nowadays functions as a bar and a desert motel with eight trailer rooms. Electricity is produced by a small generator and a telephone was not installed until 1984. Taxation is a common concern for a society: with Del Pocco the isolation out here turns into a concentrate, or a consequence, of a larger social movement toward the kind of loneliness that is being called independence.

In this desert, people can withdraw and hide themselves with their own notion of freedom. Crumpled men with suspenders and checkered shirts, and their knees curved like they were placers in a golden creek, inform us that they live up in the mountains. Their neighbours are mountain lions and peregrine falcons. How they have managed to drag lumber and trailers up those hills, nobody understands.

Over the years, though, a number of travellers have passed through Middlegate. Stephen King sat at one of the bar tables scribbling away at his book ”Desperation”. Johnny Cash came by and signed a picture of himself climbing out of a big white car.

In her enthralling book about movie pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, ”River of Shadows”, writer Rebecca Solnit dismisses the European cultural theorists, especially Baudrillard, who have described the desert landscape in western U.S. as the centre of postmodernism and the place where the future has already arrived. They should, she writes, have read the region´s history instead of staring out car windows. Rogue cops, theme parks, actor politicians and fluidly changing identities are all part of western heritage; in solitariness everything mutated most of the time, with settlers inventing themselves anew just like Muybridge´s still pictures that would start moving all of a sudden.

Light and darkness also transform everything in an environment that lies wide open to observation. As the sun slides away across the distant blue heights we experience the barren landscape as more dressed and the supply of short mesquite brush apparently is enough to keep the scattered cattle alive. We are driving into a purple, velvety twilight and approach one of the old mining towns of the desert, Eureka, where nearly all the saloons have shut out the lights. The last remaining Chinese laundry, a vague reminder of who did most of the back-breaking underground work a century ago, has closed its business, too. For breakfast the next day we get week-old muffins.

Why do people settle along the loneliest road in America? Gilbert Mair sits reading in front of his trailer:

”I grew up in Utah, where Mormon strictness make the kids revolt, joining gangs and raising hell. We wanted to get away. My son was bullied because he listened to Roy Rogers while all the others liked Ice-T and Ice Cube. We moved here so that our kids can learn some real values.”

Such as?

”You can´t get everything for free. You gotta work for it.”

He says he is applying for jobs at the road and sewer departments and at the Eureka silver mine, which has just been reopened. Zoe Ann Wilson is married to Gilbert and looks like she comes right out of a Lucinda Williams song. She wants them to place a bid on a double trailer that is for sale with three acres of land where they may have horses. Up in the mountains. Further away, got to get away.

The front town of Eureka, all side-scenes and set-pieces, is on the brink of falling apart on top of its old windblown watering-holes, and from a jukebox by a worn-down bar counter with marks from one hundred years of eager elbows a country-tinged refrain makes its way out into the street: ”Were you born an asshole/Or did you work on it all your life?”. There is, of course, another America, one that votes and joins clubs and goes to town meetings and reads international news on the web, but it just seems so very far from here.

The next day we take off north, toward the ranch territory with cowboys who call themselves buckaroos and wear silver spurs and hats with flat brims. Awaiting us are many hours of driving on dirt roads that are even lonelier and more deserted.